To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.

-Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson was born in Chanteloup-en-Brie, Seine-et-Marne, and from a young age developed a strong fascination with painting, particularly Surrealism. In 1932, after spending a year in the Ivory Coast, he discovered the Leica – his camera of choice after that moment – and began a life-long passion for photography.[1]

His camera could be wielded so discreetly that it enabled him to photograph while being virtually unseen by others. A near invisibility turned photojournalism into a primary source of information and photography into a recognised art form. This reputation began a visual journey that would revolutionize 20th-century photography. In 1933, he had his first exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York.[2]

In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his first book, Images à la Sauvette (published in English as The Decisive Moment). In it he explained his approach to photography. He states, “For me the camera is a sketch book, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, the master of the instant which, in visual terms, questions and decides simultaneously. It is by economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression.”[3]

Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the “decisive moment” — a split second that reveals the larger truth of a situation — shaped modern street photography and set the stage for hundreds of photojournalists to bring the world into living rooms through magazines such as Life and Look.[4]

He photographed dozens of luminaries: his pictures of a convalescent Matisse during World War II, of Sartre as a boulevardier and of Mahatma Gandhi minutes before he was killed have become icons of photographic portraiture. But he was also the archetype of the itinerant photojournalist during the heyday of photojournalism immediately after the war, before television became widespread, when millions of people still learned what was happening in the world through the pictures that ran in magazines like Life and Paris-Match. Part of Cartier-Besson’s skill was his practice to immerse himself in places before photographing them, to blend into and learn about their cultures.[5]

Two years after the Second World War ended, Cartier-Bresson was one of the co-founders of Magnum Photos. Along with Robert Capa, George Rodger and David “Chim” Seymour, they created Magnum to reflect their independent natures as both people and photographers. Magnum also them the ability to work outside the formulas of magazine journalism. Copyright would be held by the authors of the imagery, not by the magazines that published the work. This meant that a photographer could decide to cover a famine somewhere, publish the pictures in “Life” magazine, and the agency could then sell the photographs to magazines in other countries, such as Paris Match and Picture Post, giving the photographers the means to work on projects that particularly inspired them even without an assignment.[6]

It was important for Magnum’s photographers to have this flexibility to choose many of their own stories and to work for long periods of time on them. None of them wanted to suffer the dictates of a single publication and its editorial staff. They believed that photographers had to have a point of view in their imagery that transcended any formulaic recording of contemporary events.[7]

This is illustrated in a memorable 1962 memo addressed to “All Photographers”, as Cartier-Bresson attempted to remind the photographers of their place in the world:

“I wish to remind everyone that Magnum was created to allow us, and in fact to oblige us, to bring testimony on our world and contemporaries according to our own abilities and interpretations. I won’t go into details here of who, what, when, why and where, but I feel a hard touch of sclerosis descending upon us. It might be from the conditioning of the milieu in which we live but this is no excuse. When events of significance are taking place, when it doesn’t involve a great deal of money and when one is nearby, one must stay photographically in contact with the realities taking place in front of our lenses and not hesitate to sacrifice material comfort and security. This return to our sources would keep our heads and our lenses above the artificial life, which so often surrounds us. I am shocked to see to what extent so many of us are conditioned – almost exclusively by the desires of the clients…”[8]

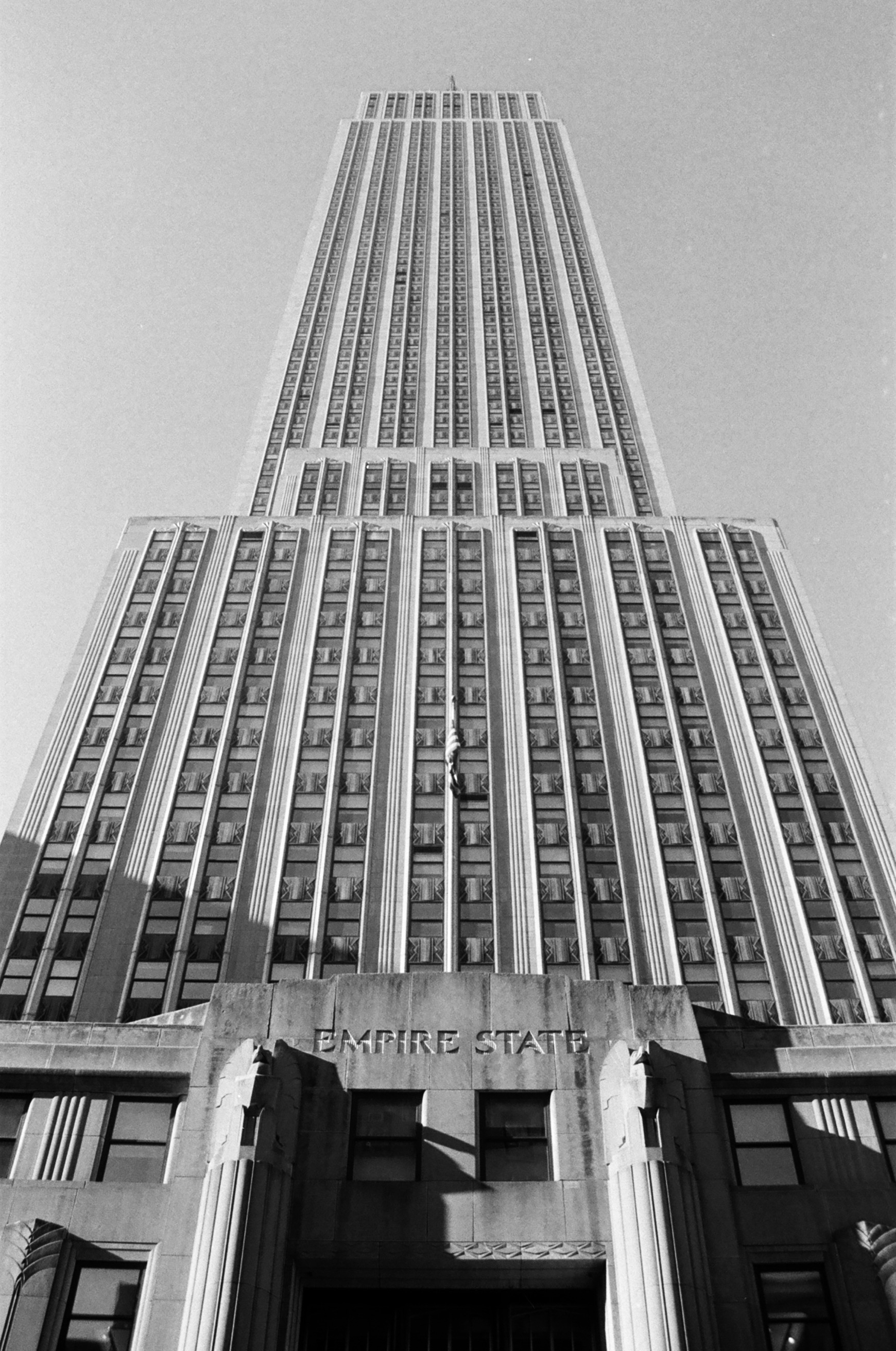

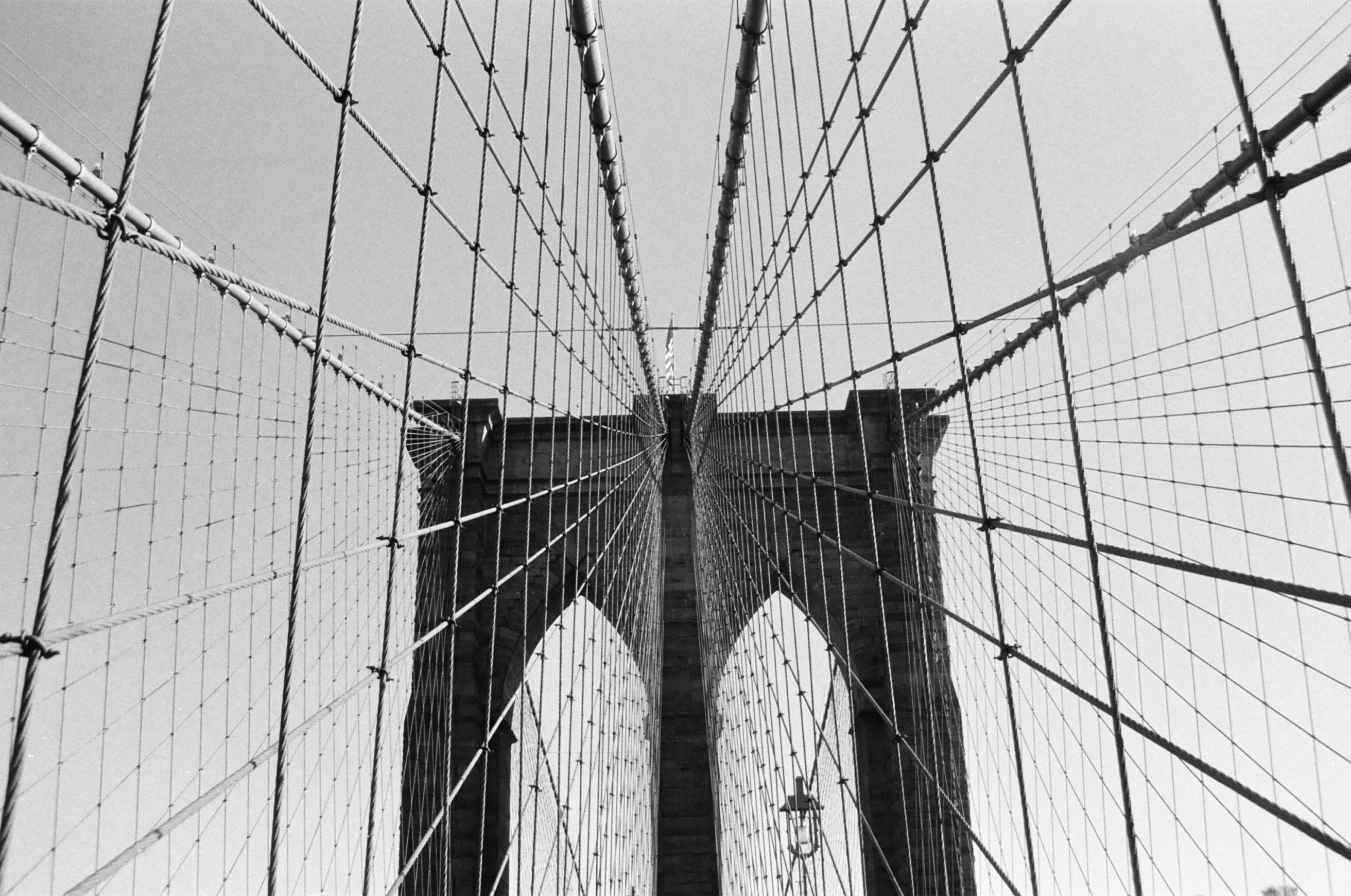

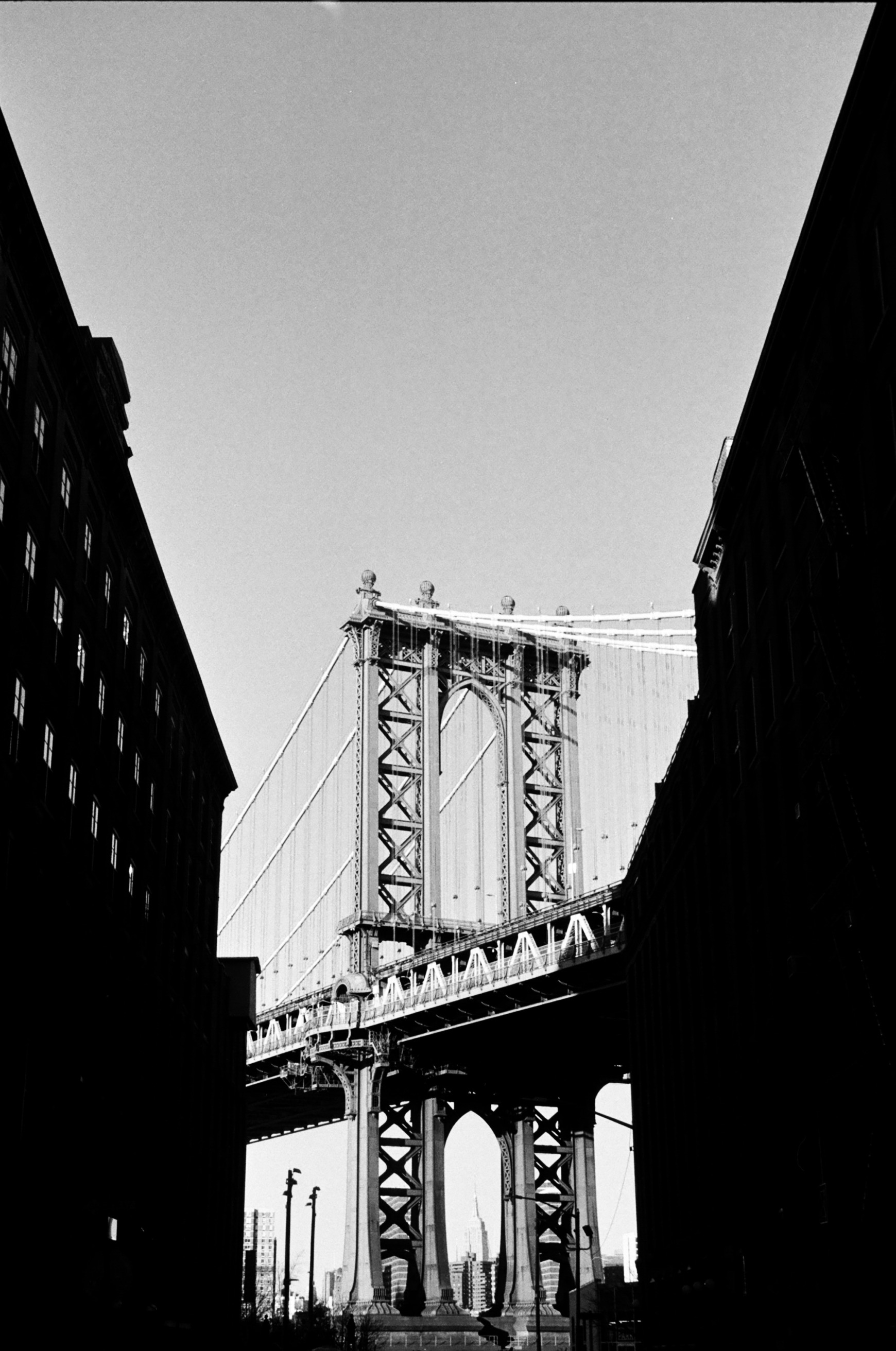

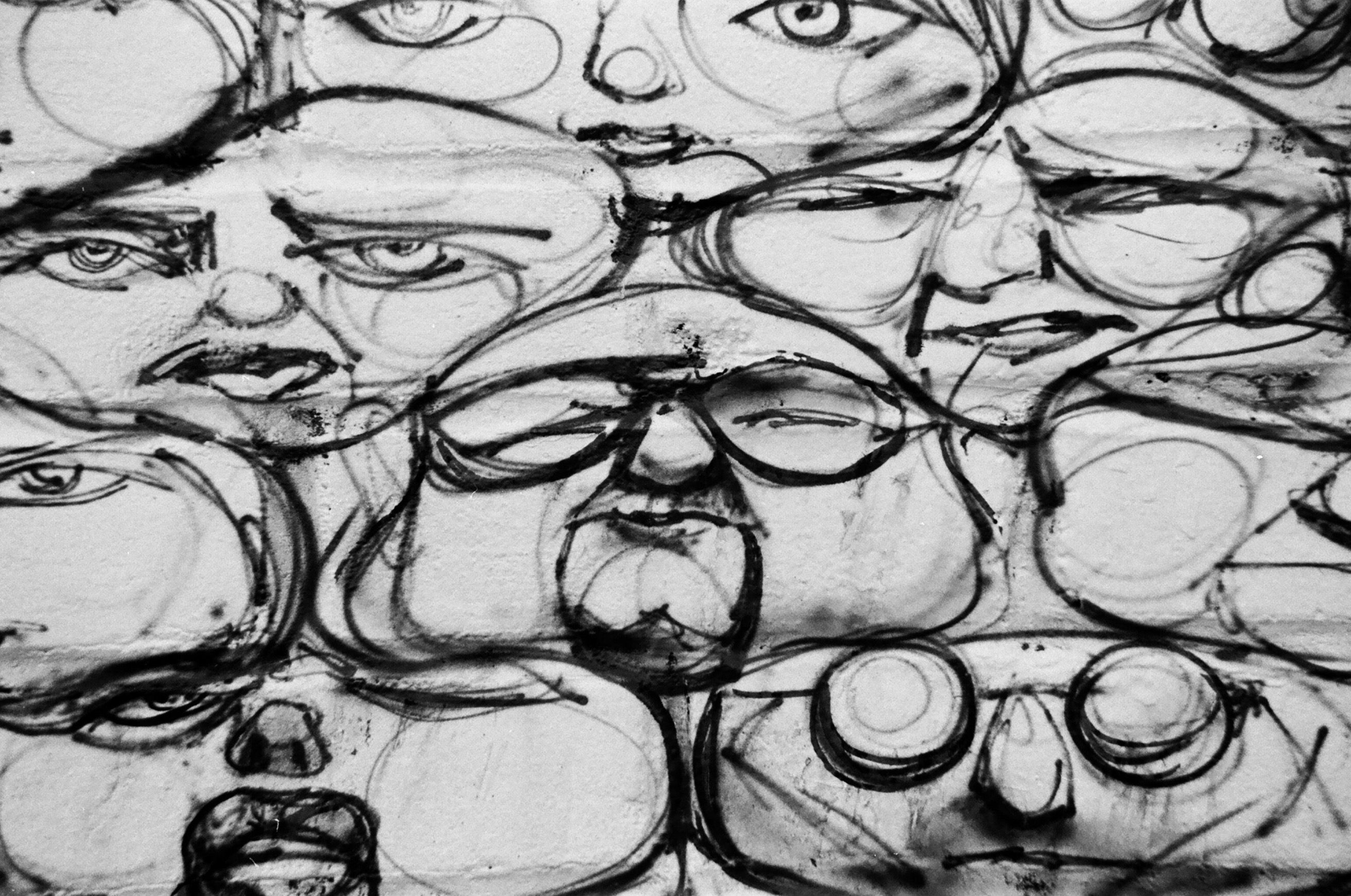

New York is one of those places where millions of “decisive moments” exist daily. It is why you could call it, street photography mecca.

The following photos are all shot on Ilford HP5 Plus 35mm film.